|

|

The History of the Christian Bible

By Melissa Elizabeth Cutler

Copyright © Melissa Cutler 2010

Available online: www.Original-Bible.com

|

|

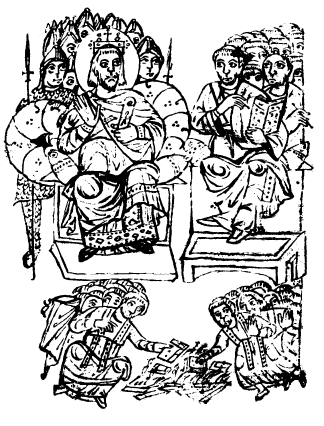

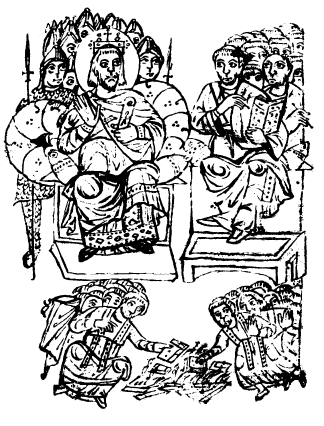

The image on the front cover is adapted from an illustration in a northern Italian compendium of canon law (c. 825). It depicts emperor Constantine and the Catholic bishops at the Council of Nicaea (325AD) overseeing the destruction of books that had been declared heretical.

Source: Jean Hubert, Jean Porcher and Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, Europe in the Dark Ages (London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 9780500030110, 1969), p. 143.

Section 1 – The Branches of Christianity 6

Section 2 – Christianity before Marcion: c.30AD to c.140AD 8

2C – The epistles of Ignatius and Polycarp 9

2D – Papias 12

2E – The Epistle of Barnabas 14

Section 3 – Early Roman Catholicism: c. 140AD to 312AD 17

3A – Justin Martyr (c.114-165AD) 19

3B – Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-202AD) 20

3C – Tertullian (c.145 AD to c.220 AD) 27

3D – Other Catholic fathers of this period 30

Section 4 – The Union of Church and State: 312AD to 480AD 32

4A – Religion and politics in Roman culture 32

4B – Constantine: the first Christian emperor 33

4C – The emperors after Constantine 35

4D – The utter corruption of the 4th century Catholic church 35

4E – Catholics who opposed violence 38

4F – The compilation of the Catholic bible 40

Section 6 – The Protestant Reformation 1517 47

6A – The corruption of the Protestant reformers 47

6B – The content of the modern bible is finally fixed 49

Section 7 – Misunderstandings and Counter Arguments 50

7A – The suppression of the bible by medieval Catholics 50

7B – The fourth century Catholics were a product their time 51

7C – God's use of evil people to achieve his plans 51

7D – Baptist, Amish and Mennonite Christians and the Donatists 52

Jesus and the apostles gave many warnings of false teaching and corruption in the church1. Jesus even hinted at the possibility that authentic Christianity might cease to exist.

Nevertheless, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?

Luke 18:8

Jesus also gave us instructions on how to identify such false teachers:

For no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit, for each tree is known by its own fruit. For figs are not gathered from thornbushes, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush. The good person out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil person out of his evil treasure produces evil, for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks.

Luke 6:34-45

In this booklet I will briefly review the history of Christianity and the bible. I will examine how beliefs and the bible have developed and changed at various points in history. I will also look at, and discuss the teachings and actions of some of the key individuals involved in these changes, applying the simple test outlined by Jesus of identifying the tree by its fruit. We shall see that many of the people responsible for giving us the bible are the very thorn bushes Jesus warned us of in the verses above, and so the mainstream Christian bible should not be trusted. As well as outlining this argument, I will discuss the counter arguments to this line of reasoning that some apologists and evangelists put forward.

I will argue that, as modern Christians, we have a duty to carefully investigate the changes that have occurred in Christian beliefs and scriptures and restore the original teachings of Christianity. I do not believe that the answer is as simple as reverting to the beliefs and writings of one of the older branches of Christianity; rather I believe we should be realistic and open minded to the idea that all branches of Christianity made mistakes during their development, and that several may have carried forward some elements of the truth.

A secondary goal of this article is to provide a review of Christian history for anyone who has little background knowledge of this subject.

This article is divided into the following sections:-

In the first section I will give a brief outline of what the main branches of modern Christianity are, and how and when they came into existence. This background information may be useful for anyone who knows relatively little about the history of Christianity.

After that I will explain the evidence that supports my argument properly in sections which examine several key eras of Christian history, examining the attitudes to scripture of people at these times. The first period of history is the early church, prior to the time of Marcion (c. 140AD).

Section three discusses the so called 'Catholic' branch of Christianity during and after time of Marcion, but before Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman empire (c. 140-312AD).

Section four discusses the period of the Christian Roman emperors who favoured Christianity and promoted it throughout the empire (312-480AD).

Section five briefly discusses developments during the middle ages.

Section six discusses the violence of the Protestant reformation and also looks at the period after it (1517 onwards).

Section seven examines and refutes counter arguments that may be put forward in response to the arguments in this article.

Section eight examines the key underlying cause of violence that has plagued both Catholic and Protestant Christianity, and how this is connected to the foundational Christian beliefs and scriptures. This section also summarises my conclusions.

There are numerous groups in the modern world which identify as Christian. The three largest are the Catholics, the Protestants and the Orthodox. The Protestant branch itself is not a unified whole, but is subdivided into numerous denominations: Anglican, Baptists, Calvinists, Lutheran, Methodists, etc., many of whom have significant points of disagreement.

The oldest of these three groups is the Catholics, dating to the second century2. In the fourth century the Catholics became very powerful and influential in the Roman empire; they used that power to spread their beliefs throughout all of Europe, persecuting and killing non-Catholics (this will be discussed in detail in section 4). It was these Catholics who decided which documents should be considered scripture and included in the bible. Initially this was a subject of heated debate, but a consensus gradually emerged during the fourth and early fifth centuries.

During the eleventh century the East-West Schism, (also known as the Great Schism) divided Christianity in Europe. The Greek speaking eastern church came to be known as the Orthodox Church, while the Latin speaking western Church continued to be know as the Catholic Church. Both groups continued to read from the same collection of 27 New Testament books.

In the 15th century Constantinople (the capital city of the Greek speaking portion of the Christian world) was defeated and captured by the Ottoman Turks. Numerous Greek speaking refugees fled into Western Europe, bringing with them knowledge of the ancient Greek language and numerous Greek copies of the bible; Greek is the original language of almost all of the New Testament and up until that time almost all western Christians had been reading from Latin translations. In the Catholic areas of Europe a renewed interest in the Greek bible developed, and many Christians begun to realise that the teachings of their church were not compatible with the bible; there was a great deal of discontent because members of the church hierarchy were using Christianity to amass wealth whist ignoring its moral teachings. This discontent lead to the Protestant reformation. This was another period of horrific violence between Christians (discussed in section 6).

The Protestant Reformation led to the creation of several new branches of Christianity most of which aimed to hold beliefs based purely on the bible. Of course the bible can be interpreted in different ways, and so despite this common underlying goal Protestantism itself has always been very fragmented. In contrast, the Catholic and Orthodox churches base their beliefs on church tradition as well as the bible, and so besides the Great Schism itself, neither of these has fragmented in the way the Protestant movement has. When the Protestants broke away from the Catholics they made changes to the bible by rejecting a number of books from the Old Testament; these books are known as the inter-testament literature, or the apocrypha. Some key Protestant figures argued for changes to the New Testament as well (Luther wanted to remove the Epistle of James, because he felt it contradicted the teaching of salvation by faith alone and not works) in the end however, no changes where made to the list of books included in the New Testament.

The bibles of Protestants, Catholics and Orthodox Christians have more in common than they have differences and all include the same 27 books in the New Testament; however it would be incorrect to say that their bibles are identical. There are differences in which books are included in the Old Testament. There are also differences of opinion about which manuscripts are most reliable, resulting in differences to the text throughout the bible. In particular, the manuscripts used by the Orthodox Church for the Old Testament are significantly different to those used by Catholics and Protestants; the Orthodox version of Daniel (for example) is significantly longer than the Catholic and Protestant versions. There are also differences in how each of these groups interpret many passages.

There were once many more branches of Christianity than the ones I have mentioned above, such as the Marcionites, Gnostics, Ebionites and Manicheans. They had scriptures that were radically different from the bibles of the Protestants, Catholics and Orthodox and there is evidence that some of these ancient Christian groups are older than Catholicism3. Those ancient groups were destroyed when the Catholics gained political power in the fourth century, a period that we shall examine in detail shortly. In this article I will say only a little about these lost rival groups and their scriptures; I will focus instead on the spiritual forefathers of modern Christianity.

When Christian evangelists, apologists and preachers write about the history of the bible they often start by looking at what the apostles themselves said about their own and each others writing, citing verses like 2 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Peter 3:14-16. Such a tactic contains the implicit assumption that the bible itself is already known to be reliable, a somewhat circular argument4. Instead of this approach, when I study the history of Christianity my main sources are the writings of people known as the Catholic fathers (or simply “church fathers”, some of the oldest are sometimes called “apostolic fathers” because they were supposedly taught by the apostles themselves). These people were all influential early Christians whose writings have been preserved by the church. From their writings we can map out a history of the development of the bible that is not dependant upon the bible itself. We will see when the various books first came to be regarded as scripture and who was involved in making those decisions.

The Catholic Church (and it's offshoots) claim that there was a succession of Christian teachers all with reasonably similar beliefs stretching right back to the apostles themselves, thus a connection is said to exist between the modern church and the apostles. If this claim were true, we should have some written record of their lives, some of their writings should have been preserved by the church, and there should be some evidence that they did indeed have beliefs and scriptures similar to those of the later church. In reality the oldest Catholic father whose writings survive is (supposedly) Clement of Rome (traditionally said to have been the fourth pope). The vast majority of writings that bear his name are universally regarded as fraudulent. There is one epistle that might have been written by him (known as 1 Clement) but even this is dogged by unanswered questions challenging its authenticity and integrity5. 1 Clement, typically dated c. 94-96AD, though if it is fraudulent it probably dates to the early mid second century.

In spite of the issues and uncertainties associated with 1 Clement, let us see what it can tell us about its author's views about scripture. The contents of the epistle indicate that the author's views about what should be considered scripture were substantially different to the views of the later church; the author frequently quotes the Jewish bible (also known as the “Old Testament”, though that term did not exist in Clement's time), the epistles of Paul, and the statements of Jesus. The epistles of Paul and words of Jesus are clearly very influential6, but only the Jewish bible is referred to as scripture7.

Interestingly, when he quotes Jesus, the statements consistently do not match the wording of any known gospel. The author gives no indication that he was working from a written source, and asks his readers to “remember” the words of Jesus (chapter 46); it is likely that he was quoting directly from oral tradition rather than written gospels.

The Didache (full English title: The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles) is another early Christian document; the identity of the author is not known, but it can still give us insights into the views of some early Christians regarding scripture.

Its author quotes from a gospel, and the wording of the quotes agrees reasonably well with the modern Gospel of Matthew. There is no indication of whether or not the author considered that book to be scripture. Also, the gospel that is quoted is referred to simply as “the gospel” (Didache 8:2 and 15:3-4) instead of “Matthew” implying that the writer had little regard for Mark, Luke and John; he may not have even been aware of the existence of those other gospels.

Ignatius and Polycarp are commonly said to have lived and written during the early second century. As with the epistles of Clement, there are numerous issues questions concerning the authenticity and integrity of these epistles.

In total there are fifteen epistles that have traditional been attributed to Ignatius and one for Polycarp; though, there is universal agreement among scholars that eight of the epistles of Ignatius are fraudulent. Furthermore, the remaining seven epistles of Ignatius exist in multiple versions: the Long Recension, the Middle Recension, and the so called “Syriac Abridgement” (three epistles only); confusingly the Middle Recension and the Syriac Abridgement are both sometimes referred to as the “Short Recension” a name that I shall avoid using.

There is unanimous agreement among scholars and historians that the epistles of the Long Recension were created by forgers interpolating and expanding the Middle Recension. A small number of scholars have argued that the “Syriac Abridgement” version is closest of the three to the original writings of Ignatius; however, the majority regard the Middle Recension as the most authentic existing version.

The text of Polycarp's epistle also contains several anomalies. Some have argued that it may be a composite of multiple letters edited together, whilst others argue that it has been greatly interpolated.

Some scholars and historians argue that none of the epistles were truly written by Ignatius or Polycarp8. Even if these epistles are fraudulent, or have suffered alteration, it is clear from their content that they come from a time when the first Catholics were only just establishing their beliefs and movement9, and so they are incredibly valuable sources of information in spite of the numerous issues surrounding them. I personally have no opinion about whether the Syriac Abridgement or the Middle Recension is the more authentic version; nor will I concern myself with the possibility that all of the epistles of Ignatius and Polycarp might be fraudulent. I will proceed by examining the epistles of the Middle Recension on the basis that even if they are fraudulent or corrupt they none-the-less must date to the second century, and can thus shed light on the attitudes of second century Catholics, regardless of other considerations.

According to the Catholic fathers who came after them10, Polycarp and Ignatius are were close friends and both were taught by the apostle John. Polycarp was bishop of Smyrna and Ignatius was bishop of Antioch. The letters are set in the rather tenuous scenario in which Ignatius is being taken by Roman guards to the arena in Rome, where he is to be killed11. During the journey, the guards permit him to be visited by Christians from the cities along the way. Ignatius supposedly used these visits to learn about the situation that local churches are in, and wrote letters which addressed those situations.

The letters indicate that everywhere Ignatius looks he is confronted by vast numbers of Christians who's beliefs are so different to his own that he hates them and considers their faith to be an abomination12; such people are described as “beasts in the shape of men” (Ignatius' Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, chapter 4) and “ravenous dogs” (Ignatius' Epistle to the Ephesians, chapter 7). The author of the epistles of Ignatius is possibly the first person known to use the identity “Catholic” (Smyrnaeans 8); thus the hatred of doctrinal diversity which would be come of typical of Catholicism can be seen here, among its earliest roots.

The epistles of Ignatius reveal another, disturbing aspect of early Christianity; many early Christians venerated martyrdom to such an extent than they actively and deliberately sought to die as martyrs. Many of them believed that having faith in Jesus meant deliberately seeking out death at the hands of the Romans. The Epistle to the Romans, indicates that some of the Christians in Rome are influential and might use their influence to save Ignatius' life, but he is eager to die, and begs them not to do this:

I write to the Churches, and impress on them all, that I shall willingly die for God, unless ye hinder me. I beseech of you not to show an unseasonable good-will towards me. Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ. Rather entice the wild beasts, that they may become my tomb, and may leave nothing of my body; so that when I have fallen asleep [in death], I may be no trouble to any one. Then shall I truly be a disciple of Christ, when the world shall not see so much as my body. Entreat Christ for me, that by these instruments I may be found a sacrifice [to God].

Ignatius' Epistle to the Romans, chapter 4

Similar sentiments are expressed in the other letters:

For, on hearing that I came bound from Syria for the common name and hope, trusting through your prayers to be permitted to fight with beasts at Rome, that so by martyrdom I may indeed become the disciple of Him “who gave Himself for us, an offering and sacrifice to God,” ye hastened to see me.

Ignatius, Epistle to the Ephesians, chapter 1

For I do indeed desire to suffer, but I know not if I be worthy to do so.

Ignatius, Trallians 4

For though I am alive while I write to you, yet I am eager to die.

Ignatius, Romans 7

Then we find this ironic statement:

Flee, therefore, those evil offshoots [of Satan], which produce death-bearing fruit, whereof if any one tastes, he instantly dies.

Ignatius in Trallians 11

Like 1 Clement and the Didache, the short version of the seven epistles of Ignatius also do not contain any indication that the author conceived of such a thing as Christian scripture. Obviously he considered the Jewish bible to be scripture, and quoted from it frequently. He also quoted from the gospels, and the epistles of Paul, but there is no indication that he considered them to be inspired; he does not introduce them with a formula of authority (i.e. “as it is written” or “the scripture says”), as he often does when quoting from the Jewish bible13. Also, we cannot take the quotations of New Testament books as an indication that there was any agreement at that time about which ones were authentic, since in Ignatius' Epistle to the Smyrnæans, chapter 3, there is a quotation from the Gospel of the Nazarenes14.

Polycarp meanwhile (if his epistle is genuine) is possibly the first person to refer to any New Testament book as scripture; in chapter 12 of his epistle he applies this term to Paul's Ephesians.

Papias was the bishop of Hierapolis; he wrote a number of works, probably in the early second century. Few details of his life are known, and his writings have not survived; though, a few small fragments of them were quoted in other documents that have survived. According to Irenaeus, Papias was taught by the apostle John15; though Papias' own statements contradict this:

But I shall not be unwilling to put down, along with my interpretations, whatsoever instructions I received with care at any time from the elders, and stored up with care in my memory, assuring you at the same time of their truth. For I did not, like the multitude, take pleasure in those who spoke much, but in those who taught the truth; nor in those who related strange commandments, but in those who rehearsed the commandments given by the Lord to faith, and proceeding from truth itself. If, then, any one who had attended on the elders came, I asked minutely after their sayings,—what Andrew or Peter said, or what was said by Philip, or by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the Lord’s disciples: which things Aristion and the presbyter John, the disciples of the Lord, say. For I imagined that what was to be got from books was not so profitable to me as what came from the living and abiding voice.

Papias16

Papias makes it clear that there are two Johns; one is the apostle who travelled with Jesus, whom he refers to in the past tense and has never met; the other is John the “presbyter” (or “elder” - “πρεσβύτερος” ) who is in a different category and is listed (by implication ranked) after “Aristion” (whoever that is). If you wish to find out more about the authorship of some of the epistles of John I suggest you now consult 2 John 1:1 and 3 John 1:1 where the author identifies himself clearly.

Papias is the first person (who's writings survive – well, sort of) to mention the names of any of the gospels; he also says a little about their authorship:

And the presbyter said this. Mark having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote

down accurately whatsoever he remembered. It was not, however, in exact order that he related the sayings or deeds of Christ. For he neither heard the Lord nor accompanied Him. But afterwards, as I said, he accompanied Peter, who accommodated his instructions to the necessities [of his hearers], but with no intention of giving a regular narrative of the Lord’s sayings. Wherefore Mark made no mistake in thus writing some things as he remembered them. For of one thing he took especial care, not to omit anything he had heard, and not to put anything fictitious into the statements.

Matthew put together the oracles [of the Lord] in the Hebrew language, and each one interpreted them as best he could.

Papias17

Whilst written gospels existed at this time, Papias' comments in the first quotation imply that oral tradition was held in higher regard. We have no reason to believe that Papias considered the gospels, or any other writings of the apostles, to be scripture.

Papias' statements about Matthew appear to be describing a sayings gospel (a list of quotes and commentary like the Gospel of Thomas or the hypothesised Quelle) rather than a narrative account of Jesus' life, as we have in the modern Matthew. There is also evidence that our Matthew was written in Greek and that it was written by adding additional material (mostly sayings of Jesus) to the Gospel of Mark. The simplest explanation for these discrepancies is that the document which Papias knew as “Matthew” was a sayings list, and that someone later combined that with Mark to create the gospel that we call “Matthew”; presumably this happened sometime in the second century. Alternatively, if the statements of Papias do not contain reliable information about the origins of Matthew and Mark then we know nothing about the authorship of those gospels.

Further evidence that Papias was not familiar with the document we call Matthew is found in fragment 3 in Anti-Nicene Fathers, volume 1. Here Papias relates an account of the death of Judas Iscariot which bears little resemblance to the accounts found in the bible (Matthew 27:3-8 and Acts 1:18-19):

Judas walked about in this world a sad example of impiety; for his body having swollen to such an extent that he could not pass where a chariot could pass easily, he was crushed by the chariot, so that his bowels gushed out.

It is remarkable that that the few small surviving fragments of Papias' writing which survive cause such challenges for the traditional account of the history of the bible. In later centuries some (such as Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea in the 4th century) came to have a very low opinion of the writings of Papias (Eusebius describes him as “a man of exceedingly small intelligence” – Historia Ecclesiastica 3:39:13). I suspect that this is why Papias' works were not ultimately preserved by the church; a great lost to our knowledge of history.

Besides Polycarp's epistle, the only Christian document of this period that refers to a New Testament book as scripture is the Epistle of Barnabas. In chapter 4 of that epistle there is a quotation of Matthew 22:14 preceded by the authoritative formula “it is written”. Many early Christians believed that the Epistle of Barnabas was the work St Barnabas (mentioned in Galatians 2:1 and frequently mentioned in Acts) and in the 3rd century some considered it scripture; this is no longer widely believed. There is considerable uncertainty about the date of this epistle, estimates range from 70AD to 130AD.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the Epistle of Barnabas is the very obvious sympathy that its author has for certain elements of Gnostic teaching. The Gnostics where one of the rival Christian groups that the Catholics considered heretics. Their teaching focused on the idea that believers must acquire hidden spiritual knowledge:

I have hastened briefly to write unto you, in order that, along with your faith, ye might have perfect knowledge.

(from chapter 1)

What, then, says Knowledge? Learn: “Trust,” she says, “in Him who is to be manifested to you in the flesh—that is, Jesus.” For man is earth in a suffering state, for the formation of Adam was from the face of the earth. What, then, meaneth this: “into the good land, a land flowing with milk and honey?” Blessed be our Lord, who has placed in us wisdom and understanding of secret things.

(from chapter 6)

No one has been admitted by me to a more excellent piece of knowledge than this, but I know that ye are worthy.

(from chapter 9)

Another interesting aspect of the Epistle of Barnabas is the author's belief that the Jews lost their covenant with God almost immediately after it was made.

And this also I further beg of you… not to be like some, adding largely to your sins, and saying, “The covenant is both theirs and ours.” But they thus finally lost it, after Moses had already received it. For the Scripture saith, “And Moses was fasting in the mount forty days and forty nights, and received the covenant from the Lord, tables of stone written with the finger of the hand of the Lord;”[Exodus 31:18, 34:28] but turning away to idols, they lost it. For the Lord speaks thus to Moses: “Moses go down quickly; for the people whom thou hast brought out of the land of Egypt have transgressed.”[Exodus 32:7, Deuteronomy 9:12] And Moses understood [the meaning of God], and cast the two tables out of his hands; and their covenant was broken, in order that the covenant of the beloved Jesus might be sealed upon our heart, in the hope which flows from believing in Him.

Epistle of Barnabas, chapter 4

This is an idea known as replacement theology. Replacement theology comes in many forms and variations, but basically it is rooted in the following line of reasoning:

(1) Christian God is the same being as the God of the Jews and Jesus is the Jewish messiah.

Therefore: (2) The the Jewish scriptures are also Christian scripture (the “Old Testament”, though this term came later – see Section 3C on Tertullian).

But: (3) The Jews reject Jesus; they say he does not fulfil the Messianic prophesies and that Christian teachings are incompatible with their scripture.

Therefore: (4) The Jews must be evil and deluded and must no longer be the chosen people of God described in the “Old Testament”.

Therefore: (5) The Covenant between God and the Jews much have been abolished; the Jews have been rejected by God and the Christian church has replaced the Jews as God's chosen people. All of the promises given to Abraham and other Jewish fathers are now applicable to the Christian church instead of the Jews.

This line of reasoning can be seen plainly in the Epistle of Barnabas; its author consistently tries to undermine the legitimacy of Judaism, whilst claiming that the Jewish scriptures are Christian documents and that they reinforce the legitimacy of Christianity.

The historical record of the Catholic Christians who existed at this time is so poor (especially when we consider the possibility that the epistles of Clement, Ignatius and Polycarp may be forgeries) that one can sensibly question whether the Catholic branch of Christianity truly existed at this time. There certainly were Christians; but, the writings of very few of them have been preserved, probably because the overwhelming majority of them must have had views highly incompatible with the views of the later church. The few documents available which actually might correspond to this period indicate that the concept of a set of “New Testament” writings was not widespread or popular; there was not even a consensus about which gospels were authoritative. Paradoxically, of the two documents that do definitively recognise the concept of apostolic writings being scripture, one shows signs of being fraudulent or heavily edited, and the other is sympathetic to elements of Gnosticism (which would later be classed as heresy). This is particularly significant, because the first person to ever compile a Christian bible (Marcion of Sinope in the early/mid second century) also held views that were in many ways similar to Gnosticism; implying that the very concept of Christian scripture may originate not with “Catholicism” but with proto-Gnostic and/or proto-Marcionite Christian communities, and migrated into Catholic communities later.

Sometime in the early to mid second century a man called Marcion of Sinope became very prominent and influential within the Christian religion. His teachings were very radically different to modern mainstream Christianity, yet were acceptable to vast numbers of Christians of that day. He became the head a group of Christians called the Marcionites; they were one one of the largest branches of Christianity at that time18.

Modern mainstream Christians (Protestants, Catholics and the Orthodox) believe that Christianity is a continuation of the ancient Jewish religion. They believe that the being which spoke to Moses and the other Jewish prophets is one and the same as the father of Jesus. The Marcionites on the other hand (though they believed that the Jewish scriptures were an accurate record of historical events) did not believe that the being described as “God” in those accounts was truly the omnipotent supreme being of the universe. They believed that the God of Judaism was separate from the father of Jesus (the true omnipotent being). They believed that the Jews had never seen or heard the father of Jesus; they believed that no-one had every known the true God until Jesus begun to reveal him to people.

Marcion was the first person to compile a Christian “bible” (though the term bible did not exist at the time). Marcion believed that only that only the writings of Paul were truly inspired; his bible consisted of one gospel (similar to Luke but significantly shorter and ten epistles of Paul (some of which were also significantly shorter than the modern versions). Marcion rejected Titus, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy and Hebrews19; there is almost unanimous agreement among professional scholars that none of these were written by Paul.

Besides having a radically different bible to the Christians that came after him, Marcion also had a radically different interpretation of it. Marcion believed that the teachings of Jesus and Paul were in opposition to the Jewish scriptures rather than supportive of them. He used contradictions between the two sets of scripture to argue his case, using passages like these:

|

And Elijah answered and said to the captain of fifty, "If I be a man of God, then let fire come down from heaven, and consume thee and thy fifty". And there came down fire from heaven, and consumed him and his fifty. 2 Kings 1:9:10 |

[Jesus' disciples] :"Lord, wilt Thou that we command fire to come down from heaven, and consume them, even as Elijah did?" But He turned and rebuked them, and said, "Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of ; for the Son of man is not come to destroy men's lives, but to save them" Luke 9:54:55 |

|

And if a woman have issue, and if her issue in her flesh be blood, she shall be put apart seven days; whosoever toucheth her shall be unclean until the even... and if a woman have an issue of her blood... beyond the time of her separation,... she shall be unclean. Leviticus 15:19, 25 |

And a woman having an issue of blood twelve years, which had spent all her living on physicians, neither could be healed of any, came up behind [Jesus], and touched the border of His garment: and immediately her issue of blood ceased. Luke 8:43,44 |

|

Therefore shalt thou make them turn their back, when thou shalt make ready thine arrows upon thy strings against the face of them (Psalm 21:12).Yea, he sent out his arrows, and scattered them; and he shot out lightnings, and discomfited them. (Psalm 18:4) Clouds and darkness are round about him... (97:2a) He sent darkness, and made it dark...(Psalm 105a). He cast upon them the fierceness of his anger, wrath, and indignation, and trouble, by sending evil angels among them (Psalm 78:49). |

Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God, that you may be able to withstand the evil one...taking the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery arrows of the wicked (Ephesians 6:16). For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this Aeon, against spiritual wickedness in high places (Ephesians 6:12) |

Quotations from Daniel Mahar's reconstruction of Antithesis20.

Obviously the modern Gospel of Luke and epistles of Paul contain many passages that contradict Marcion's teaching; however, many such passages were not present in the Marcionite version the documents. The majority of Christian scholars believe that this is because Marcion removed passages that contradicted his views; however, there is evidence that in fact the Catholics added these passages to their version of the epistles21.

I have chosen to use this event as transition point between sections 2 and 3 of this article because of the profound effect this had on Christianity as a whole. The surviving Christian writings prior to Marcion are few and far between and we can determine little of the history of Catholicism from them. There is no evidence of any consensus among them regarding the concept of Christian scripture. After Marcion's time we find numerous long and well preserved texts written by Christians who identified as “Catholic”, and mostly agreed that the writings of the apostles were scripture.

The first Christian to leave a substantial body of writings was Justin Martyr; he lived (c.114-165AD), and is considered a saint by Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and several Protestant groups. There are fourteen surviving documents that have traditionally been attributed to Justin, according to nearly universal opinion among scholars three of these are genuine and six are fraudulent; opinion is divided on the remaining five. The three authentic documents are long and developed treaties that provide a wealth of information far more substantial than the handful of epistles written by Christians prior to this time.

The writings of Justin Martyr contain quotations that appear to have come from gospels, but Justin never refers to them by their modern names. Instead he refers to them as the “memoirs of the apostles” for example:

...when [Jesus] went up from the river Jordan, at the time when the voice spake to Him, ‘Thou art my Son: this day have I begotten Thee,’22 is recorded in the memoirs of the apostles...

For in the memoirs which I say were drawn up by His apostles and those who followed them, [it is recorded] that His sweat fell down like drops of blood while He was praying, and saying, ‘If it be possible, let this cup pass:’

Both quotations are from Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 103, written in c. 142AD.

Justin Martyr is the second person to mention the name of one of the books that would later be included in the New Testament; the book of Revelations is mentioned in Dialogue with Trypho 81:4.

Justin Martyrs views were very anti-Semitic; in many ways he laid the foundation of Christian anti-Semitism that would develop over the following millennia:

For the circumcision according to the flesh, which is from Abraham, was given for a sign; that you [Jews] may be separated from other nations, and from us [Christians]; and that you alone may suffer that which you now justly suffer; and that your land may be desolate, and your cities burned with fire; and that strangers may eat your fruit in your presence, and not one of you may go up to Jerusalem.’ For you are not recognised among the rest of men by any other mark than your fleshly circumcision. For none of you, I suppose, will venture to say that God neither did nor does foresee the events, which are future, nor foreordained his deserts for each one. Accordingly, these things have happened to you in fairness and justice, for you have slain the Just One [Jesus], and His prophets before Him...

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 14

In Justin Martyr's writings we find a great deal of the development of the idea of Replacement Theology; this is the idea that the God of the Jews has abolished his covenant with them, and that the Christian church is their replacement – the new Israel, inheriting the promises that were previously made to the Jews (e.g. Genesis 13:14-15, 17:8). The very first Christian document to touch upon this idea was the Epistle of Barnabas, mentioned in Section 2E. Justin Martyr developed this idea substantially, and the Catholic fathers after him would embrace it and develop it further. Throughout history this line of reasoning has been closely linked to extreme anti-Semitism, culminating in the Nazi holocaust. We will return return to the topic of Replacement Theology as we encounter it elsewhere in the writings of the Catholic fathers.

Nor do we think that there is one God for us [Christians], another for you [Jews], but that He alone is God who led your fathers out from Egypt with a strong hand and a high arm. Nor have we trusted in any other (for there is no other), but in Him in whom you also have trusted, the God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob.… Now, law placed against law has abrogated that which is before it, and a covenant which comes after in like manner has put an end to the previous one; and an eternal and final law—namely, Christ —has been given to us [Christians], and the covenant is trustworthy, after which there shall be no law, no commandment, no ordinance.... the true spiritual Israel, and descendants of Judah, Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham…, are we [Christians] who have been led to God through this crucified Christ...

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 11

Irenaeus was bishop of Lyons, and is considered a saint by the Catholic church, Orthodox church and several Protestant groups. He was a very significant figure in the development of Catholicism; he wrote several works, but the only one that has survived complete to the present day is Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies) which was probably written between 182 and 188AD. In it Irenaeus indicates that the church of his time was swamped by the “false teachings” of Marcion and various Gnostics. The work is divided into five books; in the first Irenaeus describes the beliefs of these rival forms of Christianity; in the second he sets out to refute them; in the remaining three he explains Christian teachings that he considers “true”. In the process of doing this Irenaeus did a great deal to define the Catholic perspective of orthodoxy and heresy. He introduces numerous ideas intended to bolster the authority of “Catholic” Christianity and de-legitimise all other forms of Christianity. He argues:

That there has been an unbroken chain of Catholic bishops and teachers stretching right back to the apostles themselves, all with compatible and similar beliefs23; this concept is known as apostolic succession because the bishops are said to be the successors of the apostles.

That the Catholics preserve scriptures written by the apostles and their associates24.

That beliefs and practices of Catholic Christians thus pre-date those of heretics, and so are the original and legitimate form of Christianity25.

The blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate. Of this Linus, Paul makes mention in the Epistles to Timothy. To him succeeded Anacletus; and after him, in the third place from the apostles, Clement was allotted the bishopric. This man, as he had seen the blessed apostles, and had been conversant with them, might be said to have the preaching of the apostles still echoing [in his ears], and their traditions before his eyes. Nor was he alone [in this], for there were many still remaining who had received instructions from the apostles. In the time of this Clement, no small dissension having occurred among the brethren at Corinth, the Church in Rome despatched a most powerful letter to the Corinthians [the (probably fraudulent) epistle 1 Clement, mentioned in Section 2A], exhorting them to peace, renewing their faith, and declaring the tradition which it had lately received from the apostles, proclaiming the one God, omnipotent, the Maker of heaven and earth,... whosoever chooses to do so, may learn that He, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, was preached by the Churches, and may also understand the apostolical tradition of the Church, since this Epistle is of older date than these men who are now propagating falsehood,...

Irenaeus in Against Heresies, book 3, chapter 3, paragraph 3.

There are three problems with Irenaeus' argument.

Firstly, as discussed in Section 2, the historical record of Catholic Christianity prior to the mid second century is patchy at best. Even among the writings attributed to Justin Martyr (the last Catholic father before Irenaeus) the forgeries outnumber the authentic documents; the situation gets worse the further back we look. It is particularly interesting that Irenaeus quotes older “Catholic” documents to support his case, namely 1 Clement and the epistles of Ignatius and Polycarp; these epistles in particular show signs of forgery and fraudulent alterations.

Secondly, the few documents that we do have, contain statements that are radically out of sync with modern beliefs, and show no agreement at all on what should be considered Christian scripture26.

Thirdly, those early documents also indicate that the church then was just as permeated by widespread “heresy” then as it was in Irenaeus' time, undermining the idea that the “heresies” are younger than “orthodox” belief – the entire point of Irenaeus' argument. In spite of these flaws the arguments of Irenaeus became foundational to the identity of “Catholic” (and later Orthodox) Christianity. Irenaeus also laid the foundation for the development of the Christian bible.

Since Irenaeus views are arguments are particularly significant to the development of Christianity and the Bible I will look at two aspects of his reasoning in more detail.

Irenaeus is the first person (who's writings survive) to advocate a four gospel canon of scripture. He talks about the authorship of the four gospels he accepts in Against Heresies book 3, chapter 1, verse 1:

Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia.

Irenaeus argued against the legitimacy of any other gospels by saying that number of legitimate gospels had to be four, corresponding to the four zones of the earth and the four winds27; a somewhat fuzzy line of reasoning. The majority of Catholic fathers who came after Irenaeus accepted his conclusion that their had to be four legitimate gospels; but, to my knowledge they never re-addressed the matter of why this must be so.

Irenaeus' key point regarding scripture is that these documents derive their authority from close connection to an apostle28; the question of who wrote them is therefore a critical issue. But how can Irenaeus' (writing in the late second century) know who wrote the gospels? For Matthew and Mark, Irenaeus is repeating the statements of Papias; though adding a tiny bit of extra detail about Mark, and saying slightly less about Matthew. We have already seen (in Section 2D) that either Papias was wrong about Matthew, or the contents of that gospel have changed since Papias' time.

Irenaeus' argument is severely undermined by the fact that up until his time there is been no agreement at all among Christians about which documents should be considered scripture. To illustrate this, the table below outlines the attitude various early Christians had towards the apostle Paul:

|

Documents that do not mention the apostle Paul even once; their authors probably either rejected him, or had not heard of him: |

Writers who knew of Paul and respected him as a teacher; they quoted his letters but there is no indication that they considered them scripture: |

Early Christians who respected Paul as a Christian teacher and considered his writings to be scripture: |

|

The Didache |

The epistles of Ignatius (suspected forgeries) |

Polycarp's epistle (suspected forgery) |

|

The Epistle to Diognetus |

1 Clement (suspected forgery) |

Marcion of Sinope (a “heretic”) |

|

The Epistle of Barnabas (fraudulent but old) |

|

Basilides, Valentinus and numerous other Gnostic leaders (“heretics”) |

|

The surviving portions of the writings of Papias |

|

|

|

The surviving portions of the writings of Hegesippus |

|

|

|

2 Clement (fraudulent but old) |

|

|

|

The authentic writings of Justin Martyr |

|

|

Irenaeus' writings were extremely influential. The majority of Catholic fathers who came after Irenaeus accepted his idea of a four gospel cannon and even accepted Paul's writings as scripture (despite the fact that Paul's writings were extremely popular among Gnostics and Marcionites). Advocates of traditional Christianity often argue that from this point on there was a good consensus about which books should be considered scripture; this is somewhat exaggerated, as we shall see, but it is fair to say that after the time of Irenaeus the scriptures recognized by Christians moved a significant step closer to the New Testament that was eventually chosen.

Irenaeus quotes from many of the books that would later be included in the New Testament in a way that implies he regarded them as authoritative; however, he states that he also regards 1 Clement as authoritative (Adversus Haereses 3:3:3), and he refers to The Shepherd of Hermas as “scripture” (Adversus Haereses 4:20:2); both of these books would later be rejected from the New Testament. There is no evidence that Irenaeus had even heard of Philemon, 2 Peter, 3 John or Jude.

Irenaeus names a number of early Catholics who supposedly learned directly from the apostles, in particular: Clement of Rome (Against Heresies 3:3:3, quoted above), and also Papias and his companion Polycarp (see quotations below). Irenaeus also tells us that he himself was a disciple of Polycarp.

And these things are bone witness to in writing by Papias, the hearer of John, and a companion of Polycarp, in his fourth book; for there were five books compiled by him.

Irenaeus in Against Heresies 5:33:4.

For, while I was yet a boy, I saw thee in Lower Asia with Polycarp.... For I have a more vivid recollection of what occurred at that time than of recent events... so that I can even describe the place where the blessed Polycarp used to sit and discourse... together with the discourses which he delivered to the people; also how he would speak of his familiar intercourse with John, and with the rest of those who had seen the Lord; and how he would call their words to remembrance. Whatsoever things he had heard from them respecting the Lord, both with regard to His miracles and His teaching, Polycarp having thus received [information] from the eye-witnesses of the Word of life, would recount them all in harmony with the Scriptures. These things, through, God’s mercy which was upon me, I then listened to attentively, and treasured them up not on paper, but in my heart; and I am continually, by God’s grace, revolving these things accurately in my mind.

Irenaeus in his Epistle to Florinus29

In Section 2D I discussed Papias; Papias himself stated clearly that his information came from John “the Elder”, and that John the Apostle was already dead in Papias' day. Between Irenaeus' fuzzy childhood memories and his desperation to build an argument, he has confused John the Elder with John the Apostle; his claims about Papias and Polycarp learning directly from apostles also disintegrate; they were part of the same generation as Papias.

In reality the Christians prior to Irenaeus did not believe in a succession of bishops, all chosen by their predecessors stretching back to the apostles. If they did believe in such a thing, why didn't they ever mention it? The author of the Didache certainly wasn't familiar with this concept:

choose for yourselves bishops and deacons

Didache 15

Elsewhere in Adversus Haereses, Irenaeus gives us yet more evidence that the apostolic succession of teachings is unreliable. He reveals that his beliefs about the life and ministry of Jesus were dramatically at odds with the modern gospels; yet Irenaeus cites transmitted apostolic teachings and the gospels as his source:

Now, that the first stage of early life embraces thirty years, and that this extends onwards to the fortieth year, every one will admit; but from the fortieth and fiftieth year a man begins to decline towards old age, which our Lord possessed while He still fulfilled the office of a Teacher, even as the Gospel and all the elders testify; those who were conversant in Asia with John, the disciple of the Lord, [affirming] that John conveyed to them that information. And he remained among them up to the times of [emperor] Trajan [98-117AD]. Some of them, moreover, saw not only John, but the other apostles also, and heard the very same account from them, and bear testimony as to the [validity of] the statement.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies 2:22:430

Modern Christians believe that Jesus was 30 years old at the time of his baptism; Irenaeus also believed this, and says so in a neighbouring passage. However, the Gospel of John indicates that Jesus' ministry lasted for only three years31; this fixes Jesus' age of crucifixion at 33, give or take a year or so. It is worth noting that this is not just an insignificant detail of Jesus' life story; in Irenaeus' mind, Jesus had to live to old age as part of the process of redeeming old men32.

Why then is the apostolic tradition and scripture cited by Irenaeus so out of sync with the modern Gospel of John? There are several possibilities:

Perhaps the contents of the gospels has changed since Irenaeus' time.

Perhaps Irenaeus is wrong yet again about apostolic succession.

Perhaps he was twisting the facts to strengthen his argument against the Gnostics; this particular group had beliefs that hinged upon Jesus being about 31 at the time of the crucifixion.

The statements of Irenaeus are the only link between connecting the apostles with two of the four gospels and the early Catholic church. However, Irenaeus has demonstrated repeatedly that he is not a reliable source of information.

Irenaeus makes great claims about knowing the lineage of Catholic leaders right back to the apostles, about knowing the details of all of their teachings, and about knowing who authored the gospels. Given that Irenaeus entire argument hang on exactly these points we should be wary of bias in his statements. Another issue is how Irenaeus (writing in the late second century) could possibly know such things with the absolute certainty that he claims. We have seen that his main sources of information were oral traditions, his memory was poor, he contradicts more reliable sources of information (the writings of Papias) and his integrity is questionable. In spite of his bold claims, he is not a trustworthy source of information. This means that:-

Our only source of information about the authorship of Matthew and Mark is a fragment of the writings of Papias; see Section 2D.

We know nothing at all about the writers of the gospels commonly called “Luke” and “John”.

We know nothing about the first Catholic teachers except, perhaps, their names; surviving fragments of Papias' works are our only source on this subject too.

In spite of the dramatic flaws in Irenaeus' arguments, his formula for legitimising Catholicism and de-legitimising other forms of Christianity became foundational to Catholic (and Orthodox) identity. His arguments and basic strategy have been repeated by Catholics, and members of the off-shoots of Catholicism (the Orthodox and various Protestant churches).

Like Justin Martyr and the author of the Epistle of Barnabas, Irenaeus believed in Replacement Theology:

they who boast themselves as being the house of Jacob and the people of Israel, are disinherited from the grace of God.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3:21:1

Tertullian was the first Catholic known to conceive of Christian scripture being divided into a “New Testament” and an “Old Testament”33. “Testament” and “covenant” are old terms for a contract; these words (or rather their Greek and Hebrew counterparts) are used in the bible to describe agreements between God and humans (e.g. Exodus 19:1-8, Jeremiah 31:31, 2 Corinthians 3:14-1534 etc.), but prior to the time of Tertullian, Christians did not categorise scripture on this basis.

This change of terminology is more significant than it may at first appear. Tertullian was reacting against the teachings of Marcionite Christianity which were still one of the most widespread forms of Christianity at that time35. Marcionite Christianity is a form of Christianity that rejects the Jewish scriptures and is not attached to, or intertwined with, Judaism in the way that Protestant / Catholic / Orthodox Christianity is. In the work Adversus Marcionem (Against Marcion), Tertullian sought to argue that the Jewish Scriptures were from the same God that sent Jesus; he was in part responding to arguments laid down by Marcion in the previous century. Marcion had argued that the teachings of Jesus and Paul were fundamentally incompatible with the petty and jealous character of the Jewish God. Tertullian could not deny that the teachings of Jesus and Paul directly contradicted those of the Jewish prophets; instead, he opposed Marcionite beliefs by arguing that the incompatibilities arose because these two sets of scriptures were given at different times and for different purposes36. Tertullian argued that the Jewish God had first given the law, and then at the time of Jesus, overturned it. Hence Tertullian's distinction between the “new” scripture and “old” (outdated and overruled) scripture.

And indeed I do allow that one order did run its course in the old dispensation under the Creator, and that another is on its way in the new under Christ. I do not deny that there is a difference in the language of their documents, in their precepts of virtue, and in their teachings of the law; but yet all this diversity is consistent with one and the same God, even Him by whom it was arranged and also foretold.

Tertullian in Adversus Marcionem, book 4, chapter 1, verse 3.

Tertullian is commonly referred to as the “father of Latin Christianity”, and his ideas were pivotal to the development of Christianity and the bible; it can be argued that no Catholic father was more influential until Augustine in the 4th and 5th centuries, and Augustine himself was greatly influenced by Tertullian. It is therefore rather awkward to note that in his later days Tertullian openly advocated the views and attitudes of a radical Christian sect called the Montanists, and came to openly revile the teaching and attitudes of the more orthodox Christians of his day. The Catholic church denounced the Montanists as heretics, but Tertullian's writings were far to important to Catholicism to be cast aside, and so paradoxically he remains one of the most influential Christians of all time.

The Catholic church had good reason to reject many of the teachings of the Montanists; like Ignatius of Antioch, Tertullian was so zealous for martyrdom that his teachings encourage deliberately self-destructive behaviour. In De Fuga in Persecutione (On Running Away From Persecution) Tertullian addresses the question of whether or not it is permissible for a Christian to try to avoid persecution by fleeing to another place (something that the gospels actively encourage – Matthew 10:23).

Rutilius, a saintly martyr, after having ofttimes fled from persecution from place to place, nay, having bought security from danger, as he thought, by [bribing officials with] money, was, notwithstanding the complete security he had, as he thought, provided for himself, at last unexpectedly seized, and being brought before the magistrate, was put to the torture and cruelly mangled,----a punishment [from God], I believe, for his fleeing,----and thereafter he was consigned to the flames, and thus paid to the mercy of God the suffering which he had shunned. What else did the Lord mean to show us by this example, but that we ought not to flee from persecution because it avails us nothing if God disapproves?

Tertullian, On Running Away From Persecution, chapter 5, verse 5 (Thelwall translation).

"Him who will confess Me, I also will confess before My Father."[Matthew 10:32-33] How will he confess, fleeing? How flee, confessing? "Of him who shall be ashamed of Me, will I also be ashamed before My Father."[Mark 8:38, Luke 9:26] If I avoid suffering, I am ashamed to confess. "Happy they who suffer persecution for My name's sake."[Matthew 5:11] Unhappy, therefore, they who, by running away, will not suffer according to the divine command. "He who shall endure to the end shall be saved."[Matthew 10:22] How then, when you bid me flee, do you wish me to endure to the end? If views so opposed to each other do not comport with the divine dignity, they clearly prove that the command to flee had, at the time it was given, a reason of its own, which we have pointed out. But it is said, the Lord, providing for the weakness of some of His people, nevertheless, in His kindness, suggested also the haven of flight to them. For He was not able even without flight----a protection so base, and unworthy, and servile----to preserve in persecution such as He knew to be weak! Whereas in fact He [God] does not cherish, but ever rejects the weak, teaching first, not that we are to fly from our persecutors, but rather that we are not to fear them. "Fear not them who are able to kill the body, but are unable to do ought against the soul; but fear Him who can destroy both body and soul in hell."[Matthew 10:28]

Tertullian, On Running Away From Persecution, chapter 7, verse 2-3 (Thelwall translation)

In this way Tertullian goaded his readers to embrace a horrific fate, using threats torture in this life and the fire of hell in the next. His reasoning throughout the entire book is highly disturbing37. It is worth noting that in spite of these views, Tertullian lived to an old age; if he had died a martyr then his many admirers would no-doubt have recorded the event and we would know of it; yet his name does not feature in any of the lists of martyrs; there is no recorded account of his death as there is for so many noteworthy Christians of this period.

Tertullian also hated the Jews, and endorsed Replacement Theology; just like the Catholic fathers before and after him. Tertullian said that all Jews were guilty of the death of Jesus (An Answer to the Jews, 8:18), and that they were “divorced” from “the grace of divine favour” (An Answer to the Jews, 1:8; see also 13:13, 15, 26).

Accordingly, all the synagogue of Israel did slay Him, saying to Pilate, when he was desirous to dismiss Him, “His blood be upon us, and upon our children;” and, “If thou dismiss him, thou art not a friend of Cæsar;” in order that all things might be fulfilled which had been written of Him.

Tertullian, An Answer to the Jews, 8:18.

The Jew's at that time had recently suffered terribly at the hands of the Romans; the Jewish temple was destroyed in 70AD, and then at the time of emperor Hadrian they were driven from their land and forbidden from returning to it. Hadrian even ordered that the Jewish “promised land” be renamed “Palestine”; naming it after the Jew's ancient enemy the Philistines38 this was a strategy to mock and humiliate the Jews using their history and beliefs. Tertullian discusses the Jewish suffering without a trace of compassion anywhere in the book, and says that it is a punishment from God, because of their rejection of Jesus.

Therefore, since the Jews still contend that the Christ is not yet come, whom we have in so many ways approved to be come, let the Jews recognise their own fate,—a fate which they were constantly foretold as destined to incur after the advent of the Christ, on account of the impiety with which they despised and slew Him.

Tertullian, An Answer to the Jews, 13:24.

And because they had committed these crimes, and had failed to understand that Christ “was to be found”[Isaiah 4:6-7] in “the time of their visitation,” [Luke 19:41-44] their land has been made “desert, and their cities utterly burnt with fire, while strangers devour their region in their sight: the daughter of Sion is derelict, as a watch-tower in a vineyard, or as a shed in a cucumber garden,”—ever since the time, to wit, when “Israel knew not” the Lord, and “the People understood Him not;” but rather “quite forsook, and provoked unto indignation, the Holy One of Israel.” [Isaiah 1:7, 8, 4]

Tertullian, An Answer to the Jews 13:26, see also 13:28

Christian apologists often try to claim that there was a broad consensus about Christian scripture agreement among Christians of the second century. I do not have time to review the writings of all of the significant Christians of this era, but suffice it to say that though most of them agreed on some basic points like the authenticity of the gospels and epistles of Paul39, there was still left room for substantial areas of disagreement. There were Catholic fathers of this period who held in high regard many books that were later rejected from the canon. For example Clement of Alexandria (150 to 215AD) regarded the following books as authoritative: the Gospel of the Hebrews40, The Traditions of Matthias41, The Preaching of Peter42, 1 Clement43, The Epistle of Barnabas44 and The Shepherd of Hermas45. The Shepherd of Hermas in particular received widespread acceptance during this period46, but was rejected from the bible in later centuries.

There are a few books which were neither accepted nor debated by the early Church Fathers, there is no evidence for example that 2 Peter existed at all until 248, when it was mentioned by Origen, who said that its authenticity was doubted47. There are some phases in the writings of the Church fathers with a similar wording to statements in 2 Peter; some claim that these are allusions to 2 Peter, and use them as evidence for its existence before the 3rd century. On closer examination their case is weak; the phrasing is not identical and, given the huge volume of Christian writings from this period it can be explained by chance, and the existence of common phrases within the Christian communities that would have been used by Catholic fathers and forgers alike. Suggesting that an epistle could be well accepted for several centuries but not once mentioned by name or quoted explicitly is a somewhat desperate position.

When advocates of the mainstream bible search the writings of Christians of this period they are not able to find a single one who would agree completely with the “New Testament” that we have today.

There was however a consensus among the catholic fathers of this period about Replacement Theology, and high levels of anti-Semitism. I could not possibly embark upon a thorough discussion of the views of all of the Catholic fathers of this period, but here is one more quote to illustrate my point.

on account of their unbelief, and the other insults which they heaped upon Jesus, the Jews will not only suffer more than others in that judgment which is believed to impend over the world, but have even already endured such sufferings. For what nation is an exile from their own metropolis, and from the place sacred to the worship of their fathers, save the Jews alone? And these calamities they have suffered, because they were a most wicked nation, which, although guilty of many other sins, yet has been punished so severely for none, as for those that were committed against our Jesus.

Origen, Against Celsus, book 2, chapter 8.

By the mid 3rd century Christianity had become large and widespread throughout the Roman empire. Christians were still a minority, but by now there were many wealthy and influential Christians48 and the number of Christians was still increasing. This led the political powers of the time to feel that Christianity was a growing threat to the culture and unity of the empire, and hostility towards Christians increased dramatically towards the end of the 3rd century. Next Christians experienced the most widespread and severe persecutions that had occurred so far. In 303, emperor Diocletian and his co-rulers Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius begun to issue edicts which forced Christians to sacrifice to pagan idols; the Christian groups that were unwilling to do this (e.g. the Marcionites, Catholics, Montanists, etc.) suffered considerably.

It may seem strange that the Roman political powers felt that the unity of the empire was threatened by the growth of Christianity; however this can be explained by the fact that in Roman culture, religion and political power were closely intertwined. One of the titles claimed by the Roman emperor was “Pontifex Maximus” - head of the ancient Roman religion. The Romans were very tolerant of the pagan beliefs of the people they conquered; they believed that there were many gods, and that they all had many names; this made it very easy to integrate the beliefs of conquered people into the religion of the empire, and greatly assisted the assimilation of those people. The fact that Christians (and Jews) believed in a different God was not an issue for the Romans; however, the denial of the legitimacy of all other gods was. In the Roman mind, religion was the glue that held society together. When the Christians denied the legitimacy of the Roman gods it was mistakenly taken as denial of the legitimacy of the Roman state and the Roman emperor – treason!

The teachings of Jesus and the apostles contain a bold concept that ancient Europe was not ready to receive; their writings are consistently written from a perceptive that sees religious loyalty and political loyalty as two separate and unrelated things49. The reason for the persecution of Christians in Rome is that this concept was utterly lost on the Roman political powers and Christianity was regarded as a growing faction of traitors.

In the year 312AD emperor Constantine defeated a number of opponents and came to power in the Roman Empire. This was a dramatic turning point in the history of Christianity because Constantine was sympathetic to Catholic beliefs. In 313AD he (and his co-emperor Licinius) issued an edict (the Edict of Milan) declaring Christianity to be the “most favoured” religion in the Roman Empire50. Though the Edict of Milan declared Constantine's favouritism for Christianity, it did not force people to convert to it, and so it was a huge step forward for religious tolerance in Roman society. Sadly it was followed almost immediately by an equally dramatic step back, when Constantine issued an edict that persecution of “heretical” Christians was to be resumed. Constantine addressed the despised “heretics” directly in an open letter to inform them of their fate:

Victor Constantinus, Maximus Augustus, to the heretics.

Understand now, by this present statute, ye Novatians, Valentinians, Marcionites, Paulians, ye who are called Cataphrygians, and all ye who devise and support heresies by means of your private assemblies, with what a tissue of falsehood and vanity, with what destructive and venomous errors, your doctrines are inseparably interwoven; so that through you the healthy soul is stricken with disease, and the living becomes the prey of everlasting death. Ye haters and enemies of truth and life, in league with destruction! All your counsels are opposed to the truth, but familiar with deeds of baseness; full of absurdities and fictions: and by these ye frame falsehoods, oppress the innocent, and withhold the light from them that believe. Ever trespassing under the mask of godliness, ye fill all things with defilement: ye pierce the pure and guileless conscience with deadly wounds, while ye withdraw, one may almost say, the very light of day from the eyes of men. But why should I particularize, when to speak of your criminality as it deserves demands more time and leisure than I can give? For so long and unmeasured is the catalogue of your offenses, so hateful and altogether atrocious are they, that a single day would not suffice to recount them all....

Constantine51

The edict went on to outline that they were to be stripped of their property simply for meeting together; worse penalties were soon to follow. The pagans too suffered persecution under Constantine52.

Constantine did not officially convert to Christianity or receive baptism until he was dying in 337AD, but this did not stop him getting involved in Christian affairs. For example in 325AD, he initiated the Council of Nicaea to settle disputes about the divinity of Jesus. Though still unbaptised, Constantine participated in the discussions as though he was a bishop53.

The Council of Nicaea established the doctrine of the trinity. Constantine immediately ordered that the books of Arius and his followers be burnt on pain of death. (Arias was a bishop who opposed the doctrine of the trinity; he believed that Jesus was born an ordinary man and that he became the son of God in an adoptive sense at his baptism.) It's worth remembering that the version of Matthew 3:17 quoted by Justin Martyr in the mid second century was a version that supported Arias' beliefs (see Section 3A above); presumably any similar copies of Matthew still in circulation were now being destroyed.

This therefore I decree, that if any one shall be detected in concealing a book compiled by Arius, and shall not instantly bring it forward and burn it, the penalty for this offense shall be death; for immediately after conviction the criminal shall suffer capital punishment.

Emperor Constantine, in an epistle written immediately after the council of Nicaea. The epistle is recorded by Socrates Scholasticus (also known as Socrates of Constantinople) in Ecclesiastical History, book 1, chapter 9.

Constantine begun the process of converting the empire to Christianity, but died in 337, before this was complete. After his death the throne was inherited by his sons Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans; they initially ruled together, and then started fighting. Constantine's son's attempted improve the unity of the Catholic church by making the Catholic bishops accept the Arianists back into the fold; this bought the emperors into conflict with the church and they came to be despised by the Catholics. Constantine II died in 340AD, Constans died in 350 and Constantius II died in 361.

After the deaths of Constantine's sons, his nephew Julian became emperor. Julian was the last pagan emperor. He attempted to restore paganism to its original place as the main religion of the empire; he prevented Christians form occupying senior positions in his administration, but did not persecute Christians violently. Julian's reign was extremely short, a mere 19 months.

There followed a succession of Christian emperors who ruled for short periods of time : Jovian (8 months), Valentinian I (about a year).... The details of their lives are not particularly relevant to the history of the bible; though, it is worth mentioning that the persecution of Paganism was scaled up significantly after the death of Julian. It was at this time, over the course of a couple of decades that the number of Pagans (and there levels of wealth and influence) plummeted. Rather than focus on the laws passed against pagans54 however, I wish to focus on the attitudes and teachings of Catholics at this time. We will see that they encouraged and approved of the violence carried out on their behalf; this is far more relevant to the development of the bible, since these were the very same people who made the decisions about what should be considered scripture.

I commented at the beginning of this section that the Romans before Constantine believed that only members of the state religion could be considered loyal citizens; when the Catholics gained political influence they themselves continued to propagate this basic miss-understanding. Violence and brute force continued to be used to suppress rival religious groups and force conversions to the official religion, starting with the “heretics” and then extending to Pagan's also a little later.

Of-course some will object here, and claim that the Church was not guilty of the crimes committed in their name by the political authorities. However the writings of the bishops of the time reveal that Constantine was a very popular figure55. The Catholic Church approved of his violent actions56. Sadly there are many passages in the writings of the Catholics of this time where we find them encouraging even more violence.

But on you also, Most Holy Emperors, devolves the imperative necessity to castigate and punish this evil, and the law of the Supreme Deity enjoins on you that your severity should be visited in every way on the crime of idolatry. Hear and store up in your sacred intelligence what is God's commandment regarding this crime.

In Deuteronomy this law is written, for it says: “But if thy brother, or thy son, or thy wife that is in thy bosom or thy friend who is equal to thy own soul, should ask thee, secretly saying: Let us go and serve other gods, the gods of the Gentiles; thou shalt not consent to him nor hear him, neither shall thy eye spare him, and thou shalt not conceal him. Announcing thou shalt announce about him; thy hand shall be first upon him to kill him, and afterwards the hands of all the people; and they shall stone him and he shall die, because he sought to withdraw thee from thy Lord.” [Deuteronomy 13:6-10] 2. He bids spare neither son nor brother, and thrusts the avenging sword through the body of a beloved wife. A friend too He persecutes with lofty severity, and the whole populace takes up arms to rend the bodies of sacrilegious men.

Even for whole cities, if they are caught in this crime, destruction is decreed; and that your providence may more plainly learn this, I shall quote the sentence of the established law.... [He then quotes Deuteronomy 13:12-18]

Firmicus Maternus in De Errore Profanarum Religionum57 (346AD); this quotation is from chapter 29, entitled: “Let the Emperors Stamp Out Paganism and Be Rewarded by God”

In 408 Augustine of Hippo wrote an epistle to Vincentius, a Rogatist. (The Rogatists were a non-Catholic Christian group; they were a small offshoot of the Donatists with very similar views to that sect.) In this epistle (known as Epistle 93) Augustine discusses the key issues that Catholics and Donatists disagree on; the issue of persecution and forced conversion being foremost among these. Throughout the first 12 chapters Augustine repeatedly endorses the persecution of non-Catholics; he even praises the effectiveness of those methods for propagating Catholicism, and explains why he and his fellow Catholics endorse such cruel tactics when it serves the purpose of their religion. An English translation of this epistle can be found in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series 1, volume 1, p382-401. Here are a couple of quotes from the epistle:

Nay verily; let the kings of the earth serve Christ by making laws for Him and for His cause.